Perfect Blue (Satoshi Kon, 1997) Review

When the thin line between sanity and delirium gets blurred.

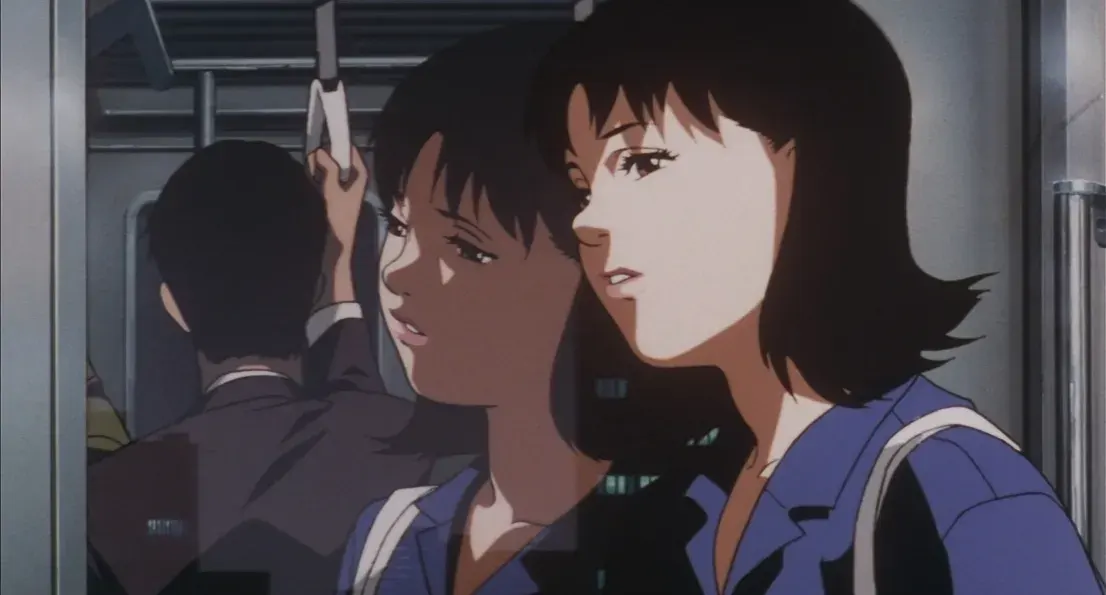

It’s 1997. The new millennium is just around the corner. Household Internet is already a reality in Japan. The mainstream mania for pop idol icons is at its peak. Mima Kirigoe (Junko Iwao) is enjoying the benefits of fame and success brought by her girl pop group CHAM! Her life seems to be colored in perfect yellow.

However, Satoshi Kon makes sure to remind that there are two sides to every coin. Instead of taking the easy way out and showing the highlights and comfortable life of a successful artist like Mima, he chose to deconstruct the Japanese pop idol archetype and delve into the darker aspects of the industry, to the point where both the singer and the viewer experience something akin to a fever dream. This downward spiral begins when Mima announces that she’s leaving CHAM! to pursue her acting career. What appears to be a fairly straightforward transition turns out to reveal the sordid underbelly of the entertainment business, which virtually forces young female stars to engage in explicit sexual content in exchange for the fame and status they seek. Not only that, but the film also dismantles the dark side of stan culture through the sinister stalker who posts Mima’s life on an online blog.

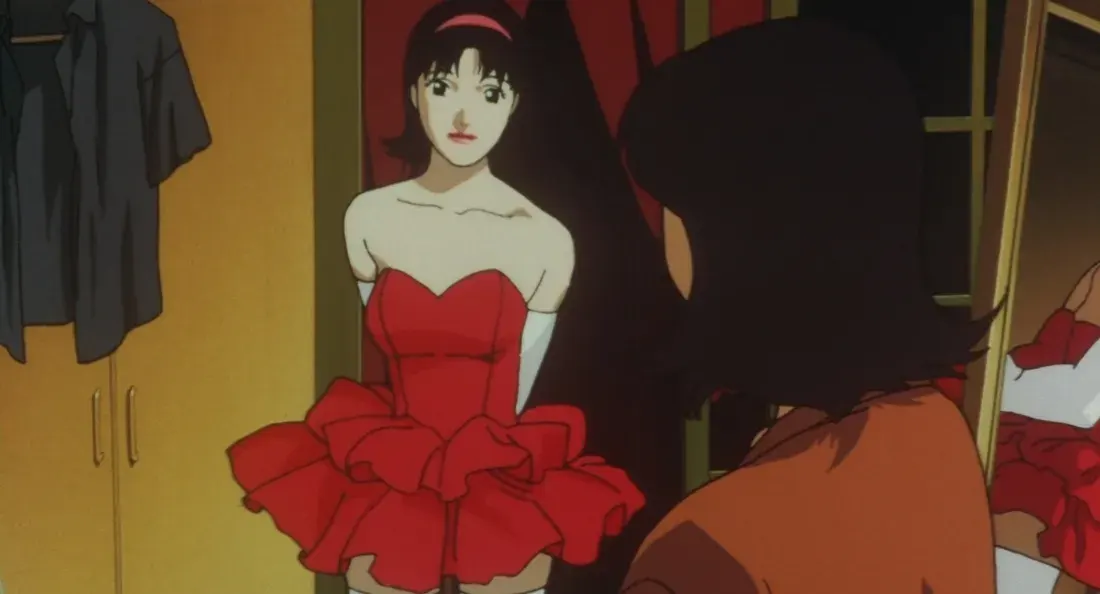

The above factors cause Mima’s personality to split into two: the blue, detached, and real persona that tries to fit into the acting industry, and the red, pop-icon, fictional persona that is a product of the blue persona’s regret and disapproval of her choices. The red part mocks the blue part for selling her soul by engaging in perverted activities such as the rape scene in the movie or the nude photo shoot, irreparably damaging her pristine image.

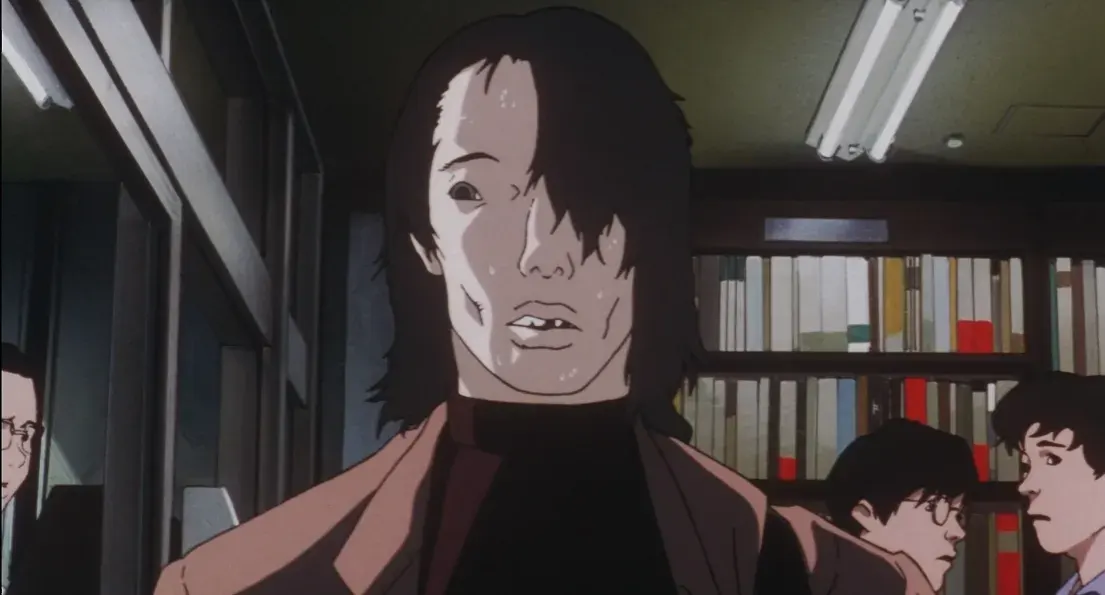

Another important figure is the creep stan, who refuses to accept Mima’s metamorphosis from the cute, sweet, innocent pop singer who exuded tenderness from every angle to a more sexualized, adult-oriented facet. He even buys every copy of the magazine that features the photo shoot to prevent others from seeing it. His disdain is so strong that he resorts to murdering members of the film crew, as if to blame them for what Mima is doing. Although the underlying motif of these stories differ, he reminded me of Björk stan Ricardo López, whose suicide happened just one year prior to the release of Perfect Blue. Quite an eerie “coincidence”, isn’t it?

The juxtaposition of the naive and cute J-pop idol with the dark and twisted sexual parts is disturbing. I’m very critical of the inclusion of explicit sex in films because it usually adds nothing to the story beyond morbidity, as I point out in my review of Poor Things. However, Perfect Blue is one of the rare films, along with Requiem for a Dream (Darren Aronofsky, 2001), that justifies its use to show how low a person can fall. The rape scene is as sickening as it gets. It’s almost as uncomfortable and repulsive as Irreversible (Gaspar Noé, 2003). Even though the scene is shorter, it doesn’t fail to make the viewer feel dead inside when watching someone as innocent and pure as Mima involved in such a depraved and wicked act. The same sentiment applies to the nude photo shoot, which is supposed to be sexually arousing, but instead elicits disgust and pity for her as she’s striving for recognition as a legitimate actress and blinded by her concept of success.

In addition, men are usually portrayed from a voyeuristic perspective, with perverted and disfigured faces. They view Mima with lust, as a mere object to satisfy their sexual desires. They contribute to her downfall by shaping the expectations of what they want from her, and thus making her try to live up to them.

As the narrative progresses, Mima’s mental deterioration worsens and the plot becomes increasingly surreal and cryptic. It gets to the point where you start laughing nervously and making funny faces due to the inability to grasp the unfolding events. Her jarring dissociation from her persona is palpable in visual details such as the orderliness of her room, as shown in the images below, and in the labyrinth of plot twists her mind creates as the line between what is real and what is not becomes completely blurred. Eventually, the plot twists repeat themselves with slight variations, gradually losing the punch of the previous ones. I understand that they are the vehicle to portray Mima’s psychological derangement and create it in the viewer, but they feel like a compilation of what ifs and strange situations that don’t develop the plot, though they are indeed amusing and mesmerizing.

Along with Neon Genesis Evangelion, Perfect Blue is the only anime I’ve seen that successfully exploits its medium to tell a story that wouldn’t have the same impact if attempted with cameras and real actors, because it would be constrained by the physical world and unable to effectively portray the hypnagogic, visceral, and confusing situations it presents. Its premise strongly defines the fictional framework within which the story develops, as it is an animated film featuring an actress acting in a movie. This is an infinite pool of devices to deceive the viewer by not clarifying what is part of the movie within the film or what is supposed to be “real”. In a similar vein, the premise of Inland Empire (David Lynch, 2006) shares parallels, albeit with cameras and real actors. Speaking of which, David Lynch is the only director who comes to mind when thinking about those who manage to create dreamy and confusing atmospheres with substance (and not for the sake of being weird).

Perfect Blue also breaks away from the abundant and annoying anime clichés that often form the crux of my criticism towards the medium. They prevent anime from reaching its full potential to tell intricate and thoughtful stories without the aforementioned physical constraints. Instead, the Japanese use this medium to present shallow and idealized fantasies as an escape door from reality. In contrast, Kon treats the audience as adults, does not over-explain the plot, and portrays adult characters without childish complexes.

Up until this part, Perfect Blue had managed to completely captivate me. It felt like meeting someone you think is your soul mate and irrationally idealizing her to the point where you imagine a whole life together. You can’t conceive how it could fall apart. But it does. Oh boy, it does. It does so hard that practically everything the film has managed to build up to this moment collapses with a resounding thud. The culprit? The ending. It stands as one of the most anticlimactic conclusions the narrative could have reached. Not only that, but it ranks among the worst endings I’ve ever seen in the medium. The blue persona inexplicably triumphs over the red one for no other reason than to end on a high note. It does end in a perfect blue, but because of the victory of the blue persona instead of the sad resolution one might envision due to the deranged mental state Mima’s blue part is in throughout the film.

What seemed to be a well thought out narrative structure with a hidden logical sequence of events, like Mulholland Dr. (David Lynch, 2001), turned out to be a smoke bomb to hide Satoshi Kon’s inadequacy to culminate a plot full of tricks to both impress and confuse the viewer. It’s as if he drowned in his own mindfuck script. Nevertheless, despite my criticism, I still recommend watching Perfect Blue, as it truly is a unique experience and succeeds in conveying the central themes mentioned in the introduction: the dark side of the industry and the stan culture. Fortunately, there exists another film that takes Kon’s premise and adapts it, and that is Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010). While it doesn’t manage to convey the sense of paranoia as well as Perfect Blue does, the narrative doesn’t become entangled in its own web of plot twists. Its resolution is much more satisfying and feels more complete as a work. I strongly recommend watching both for a broader range of stories that explore perception and self-perception.